A guide to fast voxel ray tracing using sparse 64-trees

Introduction

If you have ever tried to ray trace voxels before, you might have heard about Sparse Voxel Octrees. They are one of those ideas that are just simple and clever enough to be intriguing, but not so great to hold in practice at the basic premise.

That is to say, I was not very impressed to find from some benchmarks that even one of the state of the art ray-traversal implementations performs comparatively worse than much simpler methods based on hierarchical grids (by as much as 60%!).

Still, I realized trees have some interesting advantages over grids (some of the obvious: better memory sparseness, adaptive scaling, hierarchical metadata/flags storage, DAG-based instancing), and at that point I had spent a lot of time tweaking my previous brickmap structure that heavily relies on 64-bit masks for traversal acceleration, which ultimately led me into another couple weeks of bikeshedding a more general sparse 64-branching tree.

There doesn’t seem to be many resources about voxel ray tracing around (and the classic DDAs don’t cut it at scale), so this is my attempt at an hopefully easy to follow guide. I’ll be assuming some familiarity with voxels and graphics programming, but there’s nothing too exotic here and I’ll try my best to explain everything as concisely as I can.

Some key ideas in here are directly based on the paper “Efficient Sparse Voxel Octrees” by Laine and Karras, which is probably also the most well-known paper about voxel octrees.

Memory representation of SVTs

Sparse voxel (oc)trees save memory by representing uniform sub-partitions implicitly. For example, if all children of a node are empty or share the same material, they don’t need to be stored and the node can be pruned into a leaf. In practice, the overhead involved in actually encoding the tree can be quite high if the nodes are too small.

Let’s briefly consider how ESVO represents its 2³ nodes. The exact meaning and reasons for this layout are not super important to our comparison purposes.

// 4 bytes

struct SvoNode {

uint8_t NonLeafMask; // i-th bit indicates if i-th child is a branch, otherwise a leaf/voxel.

uint8_t ValidMask; // i-th bit indicates if i-th child exists.

uint16_t ChildPtr; // Relative offset to array of existing child nodes (+4 bytes when far).

};

Since each node can encode population of at most 8 voxels, and each node takes at least 4 bytes, we can estimate a total of around 4/8 + 4/64 + 4/512 + ... ~ 0.57 bytes per voxel in the best case, not taking into account materials and other attributes.

Now, let’s see an alternative representation that we’ll be using to represent our 64-tree nodes:

// 12 bytes

struct [[gnu::packed]] SvtNode64 {

uint32_t IsLeaf : 1; // Indicates if this node is a leaf containing plain voxels.

uint32_t ChildPtr : 31; // Absolute offset to array of existing child nodes/voxels.

uint64_t ChildMask; // Indicates which children/voxels are present in array.

};

Applying the same formula as before, we get 12/64 + 12/4096 + 12/32768 + ... ~ 0.19 bytes per voxel, or nearly 3x less than SVOs, even with the added luxury of absolute pointers (which makes construction and edits a bit easier).

Of course, this is only considering the case where most voxels are actually populated, but it seems to hold up okay in practice, as most of my tests involving non-solid voxelized models were around 60% smaller.

The idea of wide trees has been around forever (e.g. B-trees, wide BVHs), mainly in motivation to the fact that bulk access to sequential memory is much faster than to small scattered chunks.

Although we could pick any other arbitrary w*h*d branching factor, or even a generalized approach like used in OpenVDB, I really like 4³ because the child/voxel population bitmasks fit in exactly one 64-bit integer, which we can use to maintain the sparseness property by compressing child nodes and voxel data by omitting entries at unset bits (as usual), and to quickly identify larger groups of empty cells for space-skipping.

There are always tradeoffs, and in this case the main downside may the far lower de-duplication efficiency that is leveraged by DAG-based compression, since individual nodes have much higher entropy and our node layout cannot represent complete leaf paths.

Setting up

Before we start, we need to setup the rendering pipeline and actually grow some trees. I’ll give a quick overview about this here.

Building trees from flat grids

The straight forward way to do this is to recurse depth-first into every possible node to fill leaf nodes. It is possible to go the other way around and just incrementally link up leafs into the tree, but that’s probably going to be a bit more complicated and slower. Parallelization shouldn’t be too hard either and just about generating subtrees separately and connecting them into a common parent node later.

On the other hand, dynamic edits are quite a bit more complicated in the case of compressed nodes, since it will involve a pool memory allocator and manual management (dangling pointers are not fun to track down!). The basic premise is pretty simple though: to insert a leaf, split all nodes across path to target node, connect links, and done. I won’t be getting further into this here, but maybe in the future.

At large scale, it’s probably best to have many smaller trees at a top-level grid rather than a single giant tree for an entire world, because memory management and streaming becomes simpler.

I should probably also note that due to alignment, I represent node structs as a triple of uints in shader code and re-build/unpack fields on demand. The alternative would be to waste another 4 bytes (or 25% of total memory) for padding, which I guess may be a bad tradeoff due to increased bandwidth compared to a few rare accesses crossing cachelines.

But enough talk, here’s the code I use to build trees in my benchmark project, which should be clear enough to illustrate the process:

RawNode GenerateTree(std::vector<RawNode>& nodePool, std::vector<uint8_t>& leafData, int32_t scale, glm::ivec3 pos) {

RawNode node;

// Create leaf

if (scale == 2) {

assert((pos.x | pos.y | pos.z) % 4 == 0);

Brick* brick = map.GetBrick(pos >> 3); // 8³ voxel brick

if (brick == nullptr) return node; // don't waste time filling empty nodes

// Repack voxels into 4x4x4 tile

// Cells are indexed by `x + z*4 + y*16`

alignas(64) uint8_t temp[64];

for (int32_t i = 0; i < 64; i += 4) {

int32_t offset = BrickIndexer::GetIndex(pos.x, pos.y + (i >> 4 & 3), pos.z + (i >> 2 & 3));

memcpy(&temp[i], &brick->Data[offset], 4);

}

node.IsLeaf = 1;

node.ChildMask = PackBits64(temp); // generate bitmask of `temp[i] != 0`.

LeftPack(temp, node.ChildMask); // "remove" entries where respective mask bit is zero.

node.ChildPtr = leafData.size();

leafData.insert(leafData.end(), temp, temp + std::popcount(node.ChildMask));

return node;

}

// Descend

scale -= 2;

std::vector<RawNode> children;

for (int32_t i = 0; i < 64; i++) {

glm::ivec3 childPos = i >> glm::ivec3(0, 4, 2) & 3;

RawNode child = GenerateTree(map, nodePool, leafData, scale, pos + (childPos << scale));

if (child.ChildMask != 0) {

node.ChildMask |= 1ull << i;

children.push_back(child);

}

}

node.ChildPtr = nodePool.size();

nodePool.insert(nodePool.end(), children.begin(), children.end());

return node;

}

Rendering

Now we need to setup some glue code to get the pixels and shaders going. The high level overview of this goes roughly like this on most graphics APIs:

- Allocate G-buffer images (albedo, normals, depth, radiance, etc.)

- Upload tree structure and leaf voxel data to storage buffer(s)

- Once a frame,

- Update stuff (input, camera, physics, etc)

- Bind shader parameters and resources

- Dispatch ray tracing shader

- Dispatch compositing/post-processing/framebuffer-blit passes as desired

I prefer to use compute shaders instead of fragment shaders because setup is much simpler and they are more flexible, but either way, the idea remains the same: we just need to cast one (or a bunch) of rays for each pixel.

The skeleton of a very simple rendering shader may look somewhat like this:

struct DispatchParams {

VoxelTree Scene;

float4x4 InvProjMat;

float3 CameraOrigin;

ImageHandle2D<float4> OutputAlbedoTex;

};

[vk::push_constant] DispatchParams pc;

[numthreads(8, 8)]

void ComputeMain(uint2 screenPos: SV_DispatchThreadID) {

// Needed in case texture size is not aligned to workgroup size.

if (any(screenPos >= pc.OutputAlbedoTex.Size)) return;

float3 rayPos, rayDir;

GetPrimaryRay(screenPos, rayPos, rayDir);

HitInfo hit = pc.Scene.RayCast(rayPos, rayDir);

float3 albedo;

if (!hit.Miss) {

let material = pc.Scene.Palette[hit.MaterialId];

albedo = material.Color;

} else {

albedo = GetSkyColor(rayDir);

}

pc.OutputAlbedoTex.Store(screenPos, float4(albedo, 1));

}

struct VoxelTree {

Node* NodePool;

uint8_t* LeafData;

Material* Palette;

public HitInfo RayCast(float3 origin, float3 dir) {

// Magic goes here

}

}

struct Node {

uint PackedData[3];

property bool IsLeaf {

get { return (PackedData[0] & 1) != 0; }

}

property uint ChildPtr {

get { return PackedData[0] >> 1; }

}

property uint64_t ChildMask {

get { return PackedData[1] | uint64_t(PackedData[2]) << 32; }

}

}

Primary rays can be generated directly from camera parameters, but these are usually abstracted through matrices so it is easier to unproject pixel coordinates using the inverse of the view-projection matrix. It’s usually not a great idea to have translations in this matrix, otherwise motion will become jittery when far from origin because float precision decreases as magnitude grows.

void GetPrimaryRay(int2 screenPos, out float3 rayPos, out float3 rayDir) {

// nit: UV re-scaling and anti-alias jitter can be pre-baked in the matrix.

float2 uv = (screenPos + 0.5) / float2(pc.OutputAlbedoTex.Size);

uv = uv * 2 - 1;

float4 far = mul(pc.InvProjMat, float4(uv, 1, 1));

rayDir = normalize(far.xyz / far.w);

rayPos = pc.CameraOrigin;

}

Random debugging tips

This may be more of a gimmick but I usually like to wrap the shader in a pair of clockARB() calls, and then plot the differences into a heatmap of noisy “per-pixel” execution timings (which are actually per-wave or sub-group), which can be useful to check if anything is working at first. Grayscale plots usually works well enough for this, but a colored palette like Viridis looks a bit fancier.

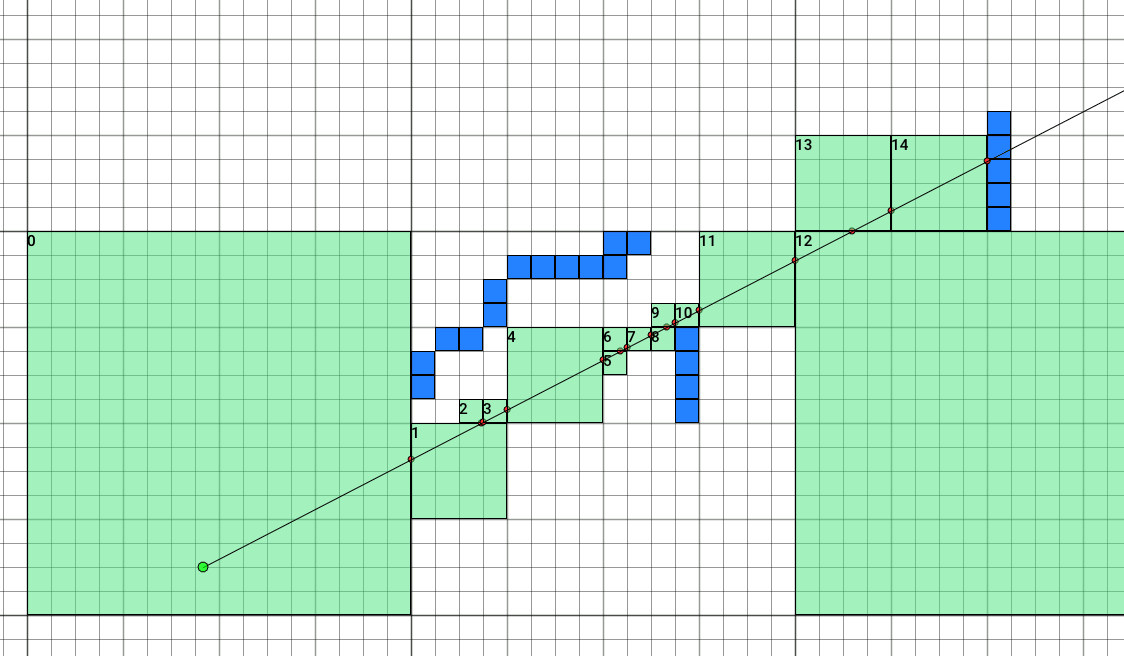

Sometimes it’s pretty hard and fiddly to track down traversal bugs just by looking at rendered output, so I often end up writing throwaway 2D visualizations using P5.js or other likes of it. (Vector math is not super ergonomic in JavaScript, so after a while I ended up quickly hacking my own thing specifically for this purpose.)

Ray-marching adaptive grids

Voxel ray tracers are typically implemented based on a DDA algorithm that incrementally steps through voxels intersecting a ray, which is relatively simple and efficient for flat grids.

In the case of trees, we want to accelerate traversal by stepping through multiple empty voxels at once rather than one voxel at a time, as determined by the tree sub-divisions.

The ESVO traversal algorithm is based on a two-fold DDA algorithm, which is relatively inefficient because it needs to incrementally adjust the ray position to intersecting child nodes as it descends the tree, in addition to actually moving the ray forward.

Instead, lets break the norm a bit and start with a very naive ray-marching algorithm, that steps over bounding boxes covering empty space on a grid (which for now will be fixed to one voxel in size):

public HitInfo RayCast(float3 origin, float3 dir) {

float3 invDir = 1.0 / dir; // pre-compute to avoid slow divisions

float3 pos = origin; // may be clamp/intersect-ed to grid bounds

float tmax = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

int3 voxelPos = floor(pos);

if (IsSolidVoxelAt(voxelPos)) break; // found hit at tmax

float3 cellMin = voxelPos;

float3 cellMax = cellMin + 1.0;

float2 time = IntersectAABB(origin, invDir, cellMin, cellMax);

tmax = time.y + 0.0001;

pos = origin + tmax * dir;

}

// ... fetch material if hit and return info

}

// AABB intersection using slab method

float2 IntersectAABB(float3 origin, float3 invDir, float3 bbMin, float3 bbMax) {

float3 t0 = (bbMin - origin) * invDir;

float3 t1 = (bbMax - origin) * invDir;

float3 temp = t0;

t0 = min(temp, t1), t1 = max(temp, t1);

float tmin = max(max(t0.x, t0.y), t0.z);

float tmax = min(min(t1.x, t1.y), t1.z);

return float2(tmin, tmax);

}

One issue with this algorithm is that it is not very robust, and the ray will immediately get stuck in place because the intersection positions won’t always fall onto the neighboring voxels, as the two side faces alias with each other and floats only have so much precision. For now, we can quickly workaround this by adding a very small bias to the intersection distances. This will result in some artifacts around voxel corners, but I’ll show a more reliable fix later.

Simplifying AABB intersection

Since we only care about the exit intersection, the full AABB intersection is redundant and can be simplified down to just three plane intersections.

One way to accomplish this, is to offset the plane to be either at the start or end vertex of the bounding box, depending on the ray direction signs. As we’ll see later, this can be simplified even further by mirroring the coordinate system to the negative ray octant.

float3 cellMin = floor(pos);

float3 cellSize = float3(1.0);

// sidePos = dir < 0.0 ? cellMin : cellMin + cellSize;

float3 sidePos = cellMin + step(0.0, dir) * cellSize;

float3 sideDist = (sidePos - origin) * invDir;

float tmax = min(min(sideDist.x, sideDist.y), sideDist.z) + 0.0001;

Another potential micro-optimization here is to re-write the intersection formula as sidePos * invDir + (-origin * invDir), which can be evaluated through 3 FMAs rather than 3 separate subtractions and multiplies. I did not find this had any considerable impact and it will increase register usage to maintain the pre-scaled origin. (Unless the shader compiler is already doing this, which I’d find a bit surprising.)

Moving to trees

Fractional coordinates

While grids are discrete and can be directly addressed in voxels units, trees can branch arbitrarily and indefinitely (within real world limits), so we don’t have a fixed unit at which we can base our coordinates on. Instead, we can naturally invert the numeric base and define each tree to be a cube in fractional range [1.0, 2.0), which is further recursively sub-divided by 1/4 as we go down the tree, following the branching factor.

One nice thing about this, is that we can take advantage of how floats are represented in memory and use bit operations to directly manipulate the mantissa, breaking it down into 2-bit chunks to address individual node cells across the tree path. This eliminates the need of expansive conversions and scaling back and forth integers that would otherwise be needed during traversal.

The reason why the range starts at 1.0 is primarily for ergonomics, since it spans at exponent zero and the decimal form can be read without considering the integral part, as the value encoded in the float will be 2^0 * (1 + mantissa/2^23).

Binary representation of IEEE754 floats, Wikipedia.

This page has an interactive converter that helped me understand by messing around: https://www.h-schmidt.net/FloatConverter/IEEE754.html

Here are some functions relying on this representation that we’ll be using during the traversal, their purpose should become clear as we progress:

static int GetNodeCellIndex(float3 pos, int scaleExp) {

uint3 cellPos = asuint(pos) >> scaleExp & 3;

return cellPos.x + cellPos.z * 4 + cellPos.y * 16;

}

// floor(pos / scale) * scale

static float3 FloorScale(float3 pos, int scaleExp) {

uint mask = ~0u << scaleExp;

return asfloat(asuint(pos) & mask); // erase bits lower than scale

}

Ray-marching trees

We can start adapting the adaptive grid ray-marcher to trees by simply inferring bounding-boxes of empty tree sub-divisions at each march step. To do this, we first need to descend down the tree from the root node until either an empty cell or a leaf is found:

Node node = NodePool[0]; // load root node

int scaleExp = 21; // 0.25 (as bit offset in mantissa)

uint childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp);

// Descend

while (!node.IsLeaf && (node.ChildMask >> childIdx & 1) != 0) {

uint childSlot = popcnt64(node.ChildMask & ((1ull << childIdx) - 1));

node = NodePool[node.ChildPtr + childSlot];

scaleExp -= 2;

childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp);

}

// Stop traversal if we have found a leaf cell

// (self-intersections can be avoided by `&& i != 0`)

if (node.IsLeaf && (node.ChildMask >> childIdx & 1) != 0) break;

Then, we just need to compute the bounding box based on the final depth:

// scale = 2.0 ^ (scaleExp - 23)

float scale = asfloat((scaleExp - 23 + 127) << 23);

float3 cellMin = FloorScale(pos, scaleExp);

float3 cellSize = float3(scale);

Now, in order to find the child cell slot in the nodes’s compressed payload array, we need to count the number of set bits preceeding the cell index in the population mask. Most shader languages don’t expose a 64-bit popcount intrinsic yet, even though most (Nvidia) hardware supports it, but it can be emulated pretty efficiently by splitting the mask into two 32-bit chunks. I’ll provide an implementation of this in the last section.

That’s all there is to our core traversal algorithm 🎉 - next, we’ll see how to make it fast and more robust.

Improving robustness

As we saw earlier, our ray-marching algorithm is not numerically robust because the intersection position will not always fall inside the neighboring voxel, and so the ray will become stuck in place. Biasing the distances is a simple but not acceptable workaround, as it results in distortions and artifacts like these:

A more reliable workaround is to clamp the position to the neighboring cell’s bounding box, which is a bit more complicated but produces acceptable results. This bounding box can be found by offseting the current cell’s bounding box with a DDA step:

float tmax = min(min(sideDist.x, sideDist.y), sideDist.z);

float3 neighborMin = select(tmax == sideDist, cellMin + copysign(scale, dir), cellMin);

float3 neighborMax = asfloat(asint(neighborMin) + ((1 << scaleExp) - 1));

pos = clamp(origin + dir * tmax, neighborMin, neighborMax); // clamp to neighbor bounds [0, 1)

Memoizing ancestor nodes

Fully descending the tree from scratch at each iteration is quite wasteful, since at each step the ray will advance to at most a sibling node of some common ancestor. One solution for this, is to maintain the lowest reachable node active between loop iterations, and gradually backtrack to ancestors as the ray moves across node boundaries.

Although we could ascend the tree through parent pointers in addition to descent, it is cheaper memory-wise to keep a small stack during traversal to remember all ancestor nodes in the currently active path.

I found it’s much faster to track node indices rather than their actual payload, and reload from the main storage buffer as needed. On some hardware, using group-shared memory for the stack instead of a “local” array may further provide a small performance boost.

uint stack[11];

int scaleExp = 21; // 0.25 (as bit offset in mantissa)

uint nodeIdx = 0; // root

Node node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

for (int i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

uint childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp);

// Descend

while (!node.IsLeaf && (node.PopMask >> childIdx & 1) != 0) {

stack[scaleExp >> 1] = nodeIdx; // save ancestor

nodeIdx = node.ChildPtr + popcnt64(node.ChildMask & ((1ull << childIdx) - 1));

node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

scaleExp -= 2;

childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp);

}

// ...

After advancing the ray, we can determine exactly which ancestor node to backtrack to by finding the index of the left-most differing bit between the mantissas of the current and next cell positions.

In code, this can be done by taking the exclusive-or between the two positions, followed by a count leading bits instruction to find the index of the highest set bit. Then, we reload the ancestor node if the changed bit represents a scale greater than that of the current node.

pos = origin + dir * tmax;

// Find common ancestor based on left-most carry bit

// We only care about changes in the exponent and high bits of

// each cell position (10'10'10'...), so the odd bits are masked.

uint3 diffPos = asuint(pos) ^ asuint(cellMin);

int diffExp = firstbithigh((diffPos.x | diffPos.y | diffPos.z) & 0xFFAAAAAA); // 31 - lzcnt, or findMSB in GLSL

if (diffExp > scaleExp) {

scaleExp = diffExp;

if (diffExp > 21) break; // going out of root?

nodeIdx = stack[scaleExp >> 1];

node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

}

And that’s it. This is the most impactful optimization we’ll be doing, and at least on my laptop’s integrated GPU, runtime on 4k res Bistro goes down from an average of 16903 cycles per ray, to about 8896 cycles - or nearly 2x faster!

Of course, the results may not be as dramatic on shallower trees and particularly in the case of brickmaps, since there’s usually only one or two indirections before reaching a leaf, so ymmv.

Coalescing single-cell skips

Since we have in hand the population bitmask of every child cell in a node, we can identify groups of empty cells and coalesce singe-cell steps almost for free. This is remarkably simple in the case of aligned 2³ cuboids, and afterwards we only need to increase the step size:

int advScaleExp = scaleExp;

if ((node.ChildMask >> (childIdx & 0b101010) & 0x00330033) == 0) advScaleExp++;

The 0x00330033 magic number is an OR-sum of all bits in a 2³ cube at zero coordinates, following the indexing order of x + z*4 + y*16.

After this, my timings are down from 8898 cycles per ray, to 7052 cycles (or 21% faster). Here’s a visualization of how this change affects march steps:

It is possible to use more sophisticated methods to identify unaligned or anisotropic cell sizes, either by adding more bit tests, or by using a lookup table to mask out never-intersecting bits starting at any of the possible cell positions and/or quantized directions.

However, based on several previous attempts, I found that increasing accuracy of cell sizes has very low impact and rarely pays off, as the overall number of iterations usually decreases only by 2-5% when using anisotropic steps.

Ray-octant mirroring

Although we have greatly simplified the AABB intersection earlier, the side planes still need to be offset depending on the ray direction at every iteration, since the cell sizes may change. If we look at the formula again, we can see that this offset is only needed when the direction components are positive:

// sidePos = dir < 0.0 ? cellMin : cellMin + cellSize;

float3 sidePos = cellMin + step(0.0, dir) * cellSize;

float3 sideDist = (sidePos - origin) * invDir;

We can simplify both the intersection and robustness-clamping formulas by “redefining” the coordinate system to the negative ray octant, which effectively bakes the offset into the coordinates.

This can be accomplished by reversing the coordinate components for which the respective directions are positive at the start of the loop, and back whenever the “true” coordinates are needed.

Instead of using three conditionals to reverse node cell coordinates (which are represented as a bit-packed set of 2-bit XZY components), we can xor with a pre-computed mask that flips the bits of each component based on the ray direction.

This works because flipping the bits of an integer bound by a power of two is equivalent to reversing its value, as a bitwise operation. More precisely, cond ? ((1<<n)-1) - x : x = x ^ m, for m = cond ? ((1<<n)-1) : 0.

uint mirrorMask = 0;

if (dir.x > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 0;

if (dir.y > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 4;

if (dir.z > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 2;

origin = GetMirroredPos(origin, dir, true);

float3 invDir = 1.0 / -abs(dir);

// ...

for (int i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

uint childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp) ^ mirrorMask;

// Descend...

// Compute next pos by intersecting with max cube sides

float3 cellMin = FloorScale(pos, advScaleExp);

float3 sideDist = (cellMin - origin) * invDir;

float tmax = min(min(sideDist.x, sideDist.y), sideDist.z);

int3 neighborMax = asint(cellMin) + select(sideDist == tmax, -1, (1 << advScaleExp) - 1);

pos = min(origin - abs(dir) * tmax, asfloat(neighborMax));

Although we could reverse float coordinates from range [1.0, 2.0] to [2.0, 1.0] simply by 3.0 - x, our upper bound is exclusive and so this will produce ever so slightly off results, which can cause some minor artifacts if the resulting hit coordinates are used for things like light bounces.

Xor-ing the mantissa produces correct results, but only for values in range [1.0, 2.0), since they span one exponent, so we need to include a fallback for the ray origin:

// Reverses `pos` from range [1.0, 2.0) to (2.0, 1.0] if `dir > 0`.

static float3 GetMirroredPos(float3 pos, float3 dir, bool rangeCheck) {

float3 mirrored = asfloat(asuint(pos) ^ 0x7FFFFF);

// XOR-ing will only work for coords in range [1.0, 2.0),

// fallback to subtractions if that's not the case.

if (rangeCheck && any(pos < 1.0 || pos >= 2.0)) mirrored = 3.0 - pos;

return select(dir > 0, mirrored, pos);

}

So, how worth was this? Well, my timings went down from 7061 cycles per ray, to 6358 cycles, so around 10% faster worth. Diminishing returns for an idea that is quite awkward to explain, but the code isn’t that scary once the idea clicks so we might as well leave it in.

Putting it all together

Quite a few of things to work out, but in the end it wasn’t so bad, was it?

Compared to ESVO, we are still missing the check to stop descending nodes once they become smaller than a pixel, which is also the basis for the “beam optimization” pre-pass, but we should be at a decent starting point.

Here’s my actual implementation in Slang, which may hopefully help clear things I couldn’t get around to explaining properly:

public HitInfo RayCast(float3 origin, float3 dir, bool coarse) {

uint groupId = spirv_asm {

result:$$uint = OpLoad builtin(LocalInvocationIndex:uint);

};

static groupshared uint gs_stack[64][11];

//uint stack[11];

uint* stack = &gs_stack[groupId][0];

int scaleExp = 21; // 0.25

uint nodeIdx = 0; // root

Node node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

// Mirror coordinates to negative ray octant to simplify cell intersections

uint mirrorMask = 0;

if (dir.x > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 0;

if (dir.y > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 4;

if (dir.z > 0) mirrorMask |= 3 << 2;

origin = GetMirroredPos(origin, dir, true);

// Clamp to prevent traversal from completely breaking for rays starting outside tree

float3 pos = clamp(origin, 1.0f, 1.9999999f);

float3 invDir = 1.0 / -abs(dir);

float3 sideDist;

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

if (coarse && i > 20 && node.IsLeaf) break;

uint childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp) ^ mirrorMask;

// Descend

while ((node.ChildMask >> childIdx & 1) != 0 && !node.IsLeaf) {

stack[scaleExp >> 1] = nodeIdx;

nodeIdx = node.ChildPtr + popcnt_var64(node.ChildMask, childIdx);

node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

scaleExp -= 2;

childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp) ^ mirrorMask;

}

if ((node.ChildMask >> childIdx & 1) != 0 && node.IsLeaf) break;

// 2³ steps

int advScaleExp = scaleExp;

if ((node.ChildMask >> (childIdx & 0b101010) & 0x00330033) == 0) advScaleExp++;

// Compute next pos by intersecting with max cell sides

float3 cellMin = FloorScale(pos, advScaleExp);

sideDist = (cellMin - origin) * invDir;

float tmax = min(min(sideDist.x, sideDist.y), sideDist.z);

int3 neighborMax = asint(cellMin) + select(sideDist == tmax, -1, (1 << advScaleExp) - 1);

pos = min(origin - abs(dir) * tmax, asfloat(neighborMax));

// Find common ancestor based on left-most carry bit

// We only care about changes in the exponent and high bits of

// each cell position (10'10'10'...), so the odd bits are masked.

uint3 diffPos = asuint(pos) ^ asuint(cellMin);

int diffExp = firstbithigh((diffPos.x | diffPos.y | diffPos.z) & 0xFFAAAAAA); // 31 - lzcnt, or findMSB in GLSL

if (diffExp > scaleExp) {

scaleExp = diffExp;

if (diffExp > 21) break; // going out of root?

nodeIdx = stack[scaleExp >> 1];

node = NodePool[nodeIdx];

}

}

PERF_STAT_INC(TraversalIters, i);

HitInfo hit;

hit.MaterialId = 0;

if (node.IsLeaf && scaleExp <= 21) {

pos = GetMirroredPos(pos, dir, false);

uint childIdx = GetNodeCellIndex(pos, scaleExp);

hit.MaterialId = LeafData[node.ChildPtr + popcnt_var64(node.ChildMask, childIdx)];

hit.Pos = pos;

float tmax = min(min(sideDist.x, sideDist.y), sideDist.z);

bool3 sideMask = tmax >= sideDist;

hit.Normal = select(sideMask, -sign(dir), 0.0);

}

return hit;

}

// Count number of set bits in variable range [0..width]

static uint popcnt_var64(uint64_t mask, uint width) {

// return popcnt64(mask & ((1ull << mask) - 1));

uint himask = uint(mask);

uint count = 0;

if (width >= 32) {

count = countbits(himask);

himask = uint(mask >> 32);

}

uint m = 1u << (width & 31u);

count += countbits(himask & (m - 1u));

return count;

}

Making pretty images

I can’t leave before showing a couple pretty pictures, so I have quickly put together a very naive diffuse-only path tracer that can generate some of them.

I won’t be explaining any of the deed here because there are already many good resources covering the basics and beyond (much of which I still haven’t gotten past through, because here I am, still playing with traversal algorithms):

- Ray Tracing in One Weekend

- Coding Adventure: Ray Tracing

- Ray Tracing with Voxels in C++ Series

- Physically Based Rendering: From Theory To Implementation

- and more…

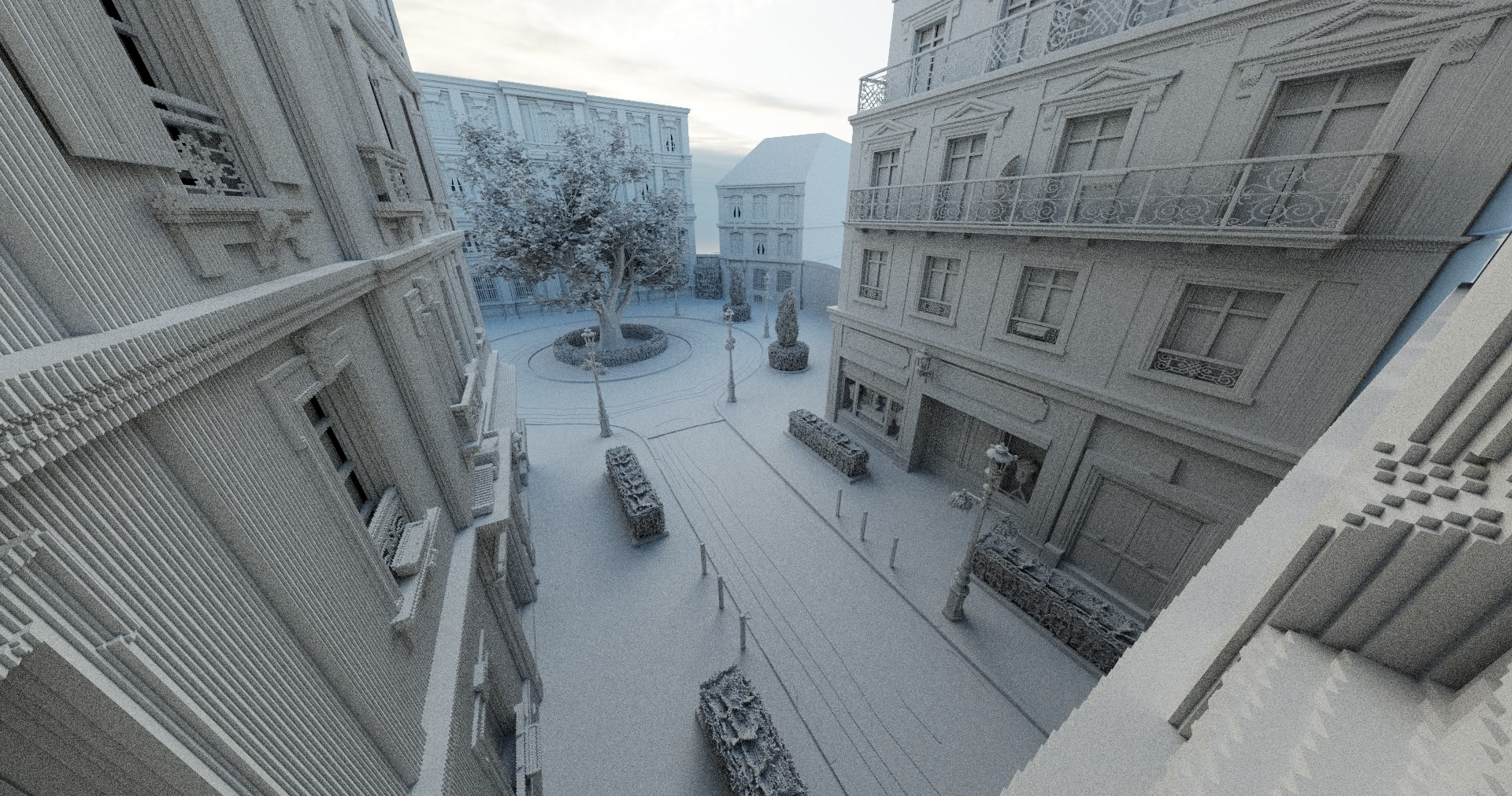

Scene is Bistro voxelized at 8k-ish resolution with materials disabled. Tree has a total of 358.33M voxels and takes 224.1MB, contains 1042.85k inner nodes, and 18545.01k leaf nodes, for ~0.62 bytes per voxel. In comparison, the same ESVO tree takes 368.0MB and ~1.02 bytes per voxel.

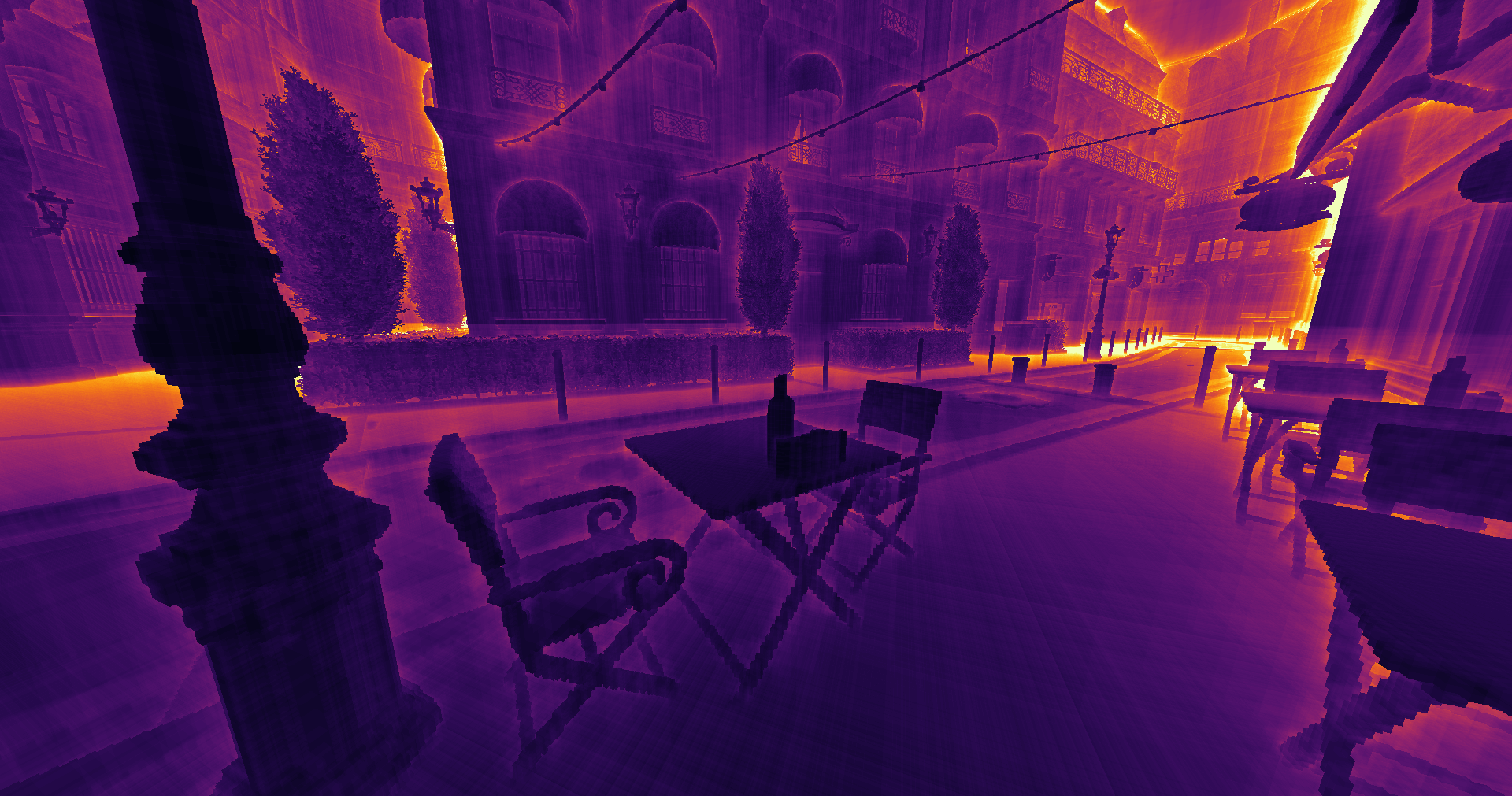

Below is a heatmap of the number of iterations for the primary ray traversal (purple 0..128 yellow). Grazing rays are a problem as with most other traversal algorithms, and especially around flat planes that don’t align with cell boundaries. One mitigation idea would be to add hull planes/AABBs to a few select nodes to emulate a crappier version of BVHs, but I really need to give a break to this stuff for now, so make what you will with any of this info.

[numthreads(8, 8)]

void ComputeMain(uint2 pos: SV_DispatchThreadID) {

InitRandom(pos, pc.FrameNo);

float3 rayDir, rayPos;

GetPrimaryRay(pos, rayPos, rayDir);

float3 radiance = 0.0;

float3 throughput = 1.0;

for (int bounceNo = 0; bounceNo < 3; bounceNo++) {

HitInfo hit = pc.Scene.RayCast(rayPos, rayDir);

if (!hit.Miss) {

let material = pc.Scene.Palette[hit.MaterialId];

throughput *= material.Color;

radiance += throughput * material.Emission;

} else {

radiance += throughput * GetSkyColor(rayDir);

break;

}

rayDir = normalize(hit.Normal + GetRandomSphereDir());

rayPos = hit.Pos;

}

float3 prevRadiance = pc.OutputAlbedoTex.Load(pos).rgb;

float weight = 1.0 / (pc.FrameNo + 1);

pc.OutputAlbedoTex.Store(pos, float4(lerp(prevRadiance, radiance, weight), 1));

}

float3 GetRandomSphereDir() {

float2 u = (NextRandomU32() >> uint2(0, 16) & 65535) / 65536.0;

float phi = u.x * 6.283185307179586;

float y = u.y * 2 - 1;

float r = sqrt(1.0 - y * y);

return float3(sin(phi) * r, y, cos(phi) * r);

}

// PCG random

static uint g_RandomSeed = 0;

uint NextRandomU32() {

uint state = g_RandomSeed * 747796405u + 2891336453u;

uint word = ((state >> ((state >> 28u) + 4u)) ^ state) * 277803737u;

return g_RandomSeed = (word >> 22u) ^ word;

}

void InitRandom(uint2 pos, uint frameNo) {

g_RandomSeed = pos.x ^ (pos.y << 16);

NextRandom();

g_RandomSeed ^= frameNo * 1234;

}